Why are paint colors different from light or digital colors?

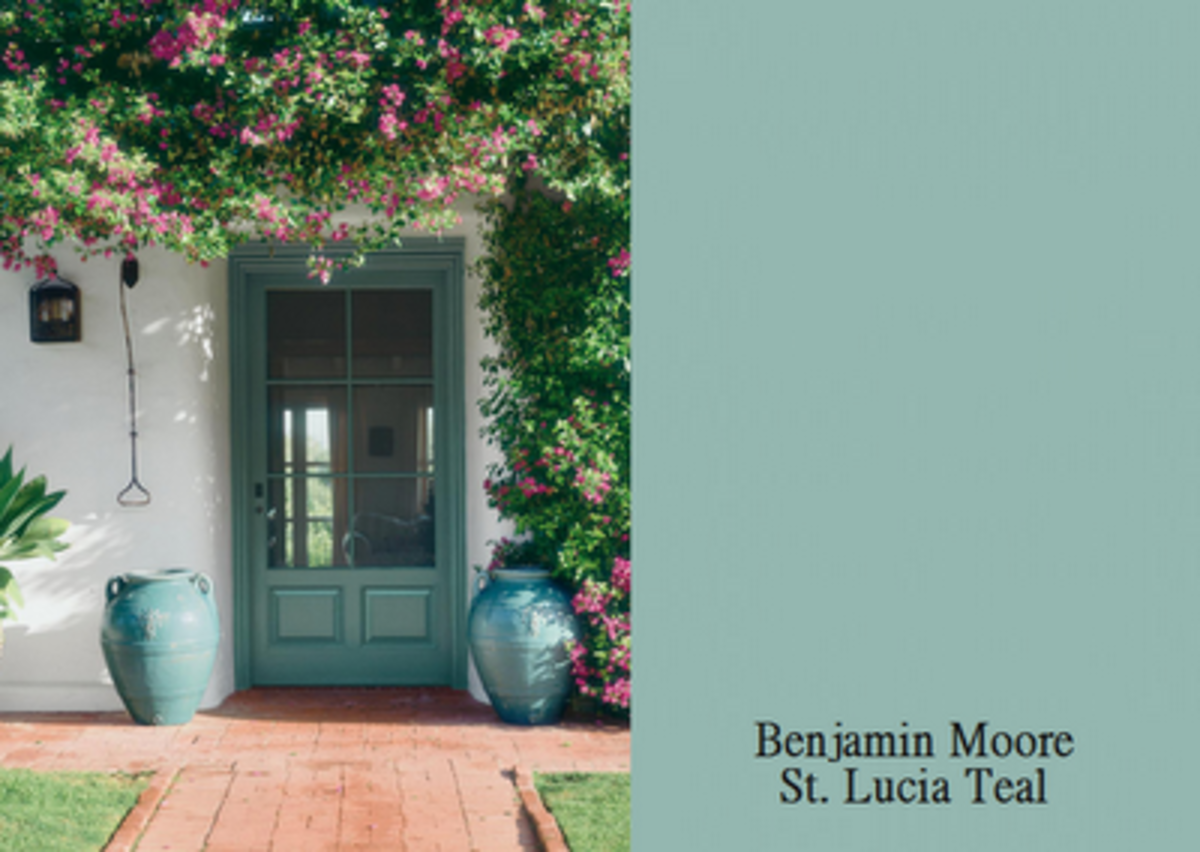

Color testing with natural pigments

If white is all colors, why do all my paints together make a blackish mess?

When speaking of light, Newton described white light as composed of all colors.

Black is the absence, not of color, but of light.

In very dim light, the color sense of the eye has nothing to report, but sensitive rods will still pick up patterns of light and dark. The dim surroundings appear leached of color. But it is not the color which has gone away; it is the light.

Dark objects (including the earths used to make your paints) absorb some or all colors of light; what is released back to the eye is the color of light we perceive. Pale objects absorb less and reflect many more colors, so we see them as white or nearly white. Powders and fine particles like snow or broken glass appear white because they scatter all colors equally toward our eyes; if only one color of light shines on them, like clouds at sunset, they appear to take on that color.

Bright art is attractive.

Paint pigments are expensive. Pure, strongly colored minerals are found naturally only in rare places on Earth, and artificial brightly-colored chemicals can be unreliable for longevity.

If an artist uses white paper, (which can be made cheaply with bleach, white clay, or many kinds of white paints), it is possible to create luminous bright paintings, that last a long time, by using only a small amount of the more expensive mineral paints.

A thin layer of paint over a white background allows light to penetrate and reflect through the paint, producing deeper colors with less pigment. Because this is the common practice, most good paint sets offer the darkest colors, which can be thinned down to give white effects. Printers inks use a similar effect, with four specially chosen artificial pigments that compliment the colors used in digital art. Cheap paints, or materials like chalk pastels that are designed for drawing on a dark background, will have more white pigments.

Mixing all the colors of a dark (watercolor) paint set together naturally absorbs most colors of light, leaving a dark mess.

If you mix many colors of pale paint (such as housepaint) together, you will get a pale mess such as grey or beige, or many other colors typically used in hospitals.

The very bright artificial pigments such as food dyes, when mixed, rarely produce a true black effect. Instead you get a 'chromatic grey' which may appear brownish/dark orange, greenish, or purplish depending on the strengths of the mixed colors. But add enough of any color, and you get a blackish effect; many commercial 'black' inks are really a dark purple when diluted.

We like to simplify light and color into 'primaries' of three: three colors for mixing any shade of paint, three colors for making any shade of light on our digital screens.

But we are only fooling ourselves: these primaries are just close approximations to differently stimulate the three different color sensors in the human eye. 'Matched' colors made of different pigments may appear very different under a new light. And some people have slightly different sensitivities to color, particularly the 'red' cone, so you can't even fool all the people equally all the time.

Honeybees, snakes, and other creatures can see very different ranges of colors than we do. A bee or grazing animal might see nothing attractive at all in a painted flower, since its mineral color signature would likely appear quite different from natural chlorophyll or "bee purple" flower markings. Yet they might well be fooled by a plastic imitation that looks unnatural to our own eyes.

Digital cameras are actually a pretty good biomimicry of the human retina:

Three different types of color sensors (made with three different chemical compositions of material, just like our eyes have differently-pigmented cone cells) are exposed to light. Where all three register, the image stores a white point; where they register at different strengths, a color is recorded; where no light shines, no color registers, and the net effect is black.

The size and focus of the image are controlled by moving a lens, or multiple lenses, just as in the human eye. Human vision has an additional type of cell, the rod, which is much more sensitive than color vision. Normally in strong light the rods are bleached out and register all the time, and the brain ignores them. But if the light drops to a low level, once the rods re-set, we can see faintly in the darkness where no color vision is possible.

To produce a wide range of color effects with minimal hardware, computer screens use codes for how much colored light to put out. Printer inks use subtractive colors (yellow, cyan (bright blue) and magenta (bright pinkish-red), and the computer uses the opposite additive colors (Red, Green, Blue). Color codes specify how much red RR Green GG and Blue BB to use: RRGGBB. 000000 is no light (we see a dark, black spot on the screen); FFFFFF is full amounts of every color (we see white). FF0000 is red, 00FF00 is green, and 0000FF is pure blue. When the image is sent to a printer, a conversion occurs, and where FF0000 indicated red in the digital image, the printer will use all but the opposite ink: leaving out the cyan, the printer will combine magenta and yellow to print a cheerful red image. If the colors are dark, like 440000 for a dim, brick-ish red on the computer screen, the printer adds black ink to darken the color. If the color is bright, like FF8888 for a bright pinkish red on the screen, the printer will simply use less ink in the proper proportions, so the paper shines through.

The real mystery is how computer makers are able to produce displays from so many different materials (liquid crystal, phosphorescent CRT, fluorescent back-lights, LEDs) that can display images using the same color codes, and can be electronically re-set at the speeds demanded by the human eye. Research chemists spend many years finding a new, colorful material that happens to be just the right shade to allow yet another form of digital display.

In historic times, whole cities could make great profits by controlling the secret of manufacturing a brilliant dye or pigment color that would make unique clothing, paints, or furnishings. Rare elements like gold, cadmium, cobalt, and copper provide the ingredients for colorful arts such as pottery, stained glass, or enamel work, and each art form demands a slightly different set of minerals or chemicals to produce its greatest range of colors.

Every pigment has a unique chemical signature. Many materials that appear dull or grey to our limited sight, would appear brilliant and unusual if our color vision could detect a broader variety of light.